I was shot down at Wiesbaden.

We were bombing Wiesbaden; that was our target. That last trip I made; Wiesbaden appeared to me like an easier target than the Ruhr Valley was. What we were after was kind of a camp where German soldiers rested; they were taken care of if they were overtired. Butcher Harris, as we called him, was head of the whole air force, Royal and Canadian. He was a tough guy and he had no mercy on whether it was civilians or recuperating soldiers that we bombed.

From: THE R.C.A.F. OVERSEAS THE SIXTH YEAR

February 1945

“In February the curve of No. 6 Group’s bomber effort began to rise once more. On ten nights during the month Canadian heavy bombers were over Germany, making sixteen attacks on oil, industrial, rail and tactical targets. In addition there were four daylight raids, one of which was abortive, and seven sea-mining operations. More than 2220 Halifaxes and Lancasters were despatched on these missions, during which 5920 tons of high explosives and incendiaries and 245 tons of mines were released. The totals of operations, aircraft and bomb tonnage represented an increase of approximately two-thirds over the previous month. On the other hand, relative losses showed a decrease. Twenty-three bombers were missing over enemy territory and ten more crashed in Britain or on our side of the lines. The R.C.A.F. Pathfinder squadron helped to mark the target on thirteen attacks in which No. 6 Group was engaged and on four other occasions when the Canadian Group was not represented. During these operations it lost three Lancasters. In air combats the Group’s bomber crews destroyed eleven enemy fighters, roughly one-fourth of the total number claimed by Bomber Command, and were credited with two probables and two damaged. An improvement in the weather, which had permitted large-scale offensive operations during the last days of January, continued through the first week of February. No. 6 Group was active five nights out of the eight, making three double attacks and two single operations. The first two-barrelled effort was against Mainz and Ludwigshafen on the 1st/2nd, when Bomber Command sent out over 1100 aircraft. The attack on Ludwigshafen, following closely upon a raid by the U.S.A.A.F., was carried out by a force of more than 350 Lancasters which included about 70 kites from No. 6 Group and the Vancouver Squadron. For the Tigers and Porcupines it was a noteworthy occasion, being their first operation on Lancs after a year on Halifaxes.

Conditions were none too favourable for their inaugural effort. There was considerable cloud over the target, forcing most of the crews to bomb on the skymarkers. Through breaks in the cloud layer some were able to pick out the target indicators, while others used the glow on the clouds as their guide. As was to be expected the bombing was somewhat scattered at first, but by the close of the attack large fires were taking hold in the eastern end of the town, enabling some crews to distinguish buildings and streets through gaps in the clouds. In addition to the usual flak defences enemy night fighters were encountered, dropping flares along the bomber’s route. One Jerry, possibly an Me. 410, attempted to attack a Lanc of the Moose Squadron over the target area only to meet a blast of return fire which set off a large bright explosion. For a moment the enemy fighter was lost from sight in the smoke over Ludwigshafen; then it again came into view, a blazing streak arching down through the night sky. F/O D. W. Storms, D.F.M., was the victorious mid-upper gunner. A brush with another Jerry rounded out an exciting sortie for a Bluenose crew skippered by F/L L. E. Coulter. On the outward flight one engine failed, but this did not deter Coulter from continuing to the target.

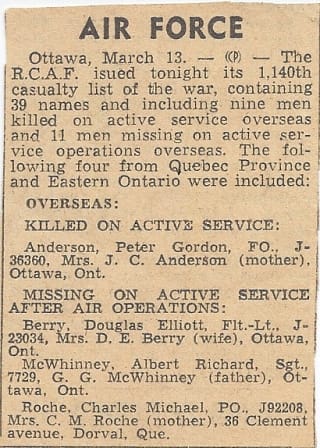

Over Ludwigshafen a fault in the electrical circuit started a small fire in the bomb-aimer’s compartment. This was extinguished, the target was bombed, and course was set for base. During the return flight an enemy fighter attempted to close in, but Coulter skillfully evaded it and reached base. He subsequently received the D.F.C. The enemy defences brought down a number of bombers, but the only loss suffered by the R.C.A.F. was a Porcupine Lancaster which crashed near base on its return. S/L H. K. Stinson, D.F.C., a second tour captain, F/O D. J. McMillan, P/Os J. T. McShane, R. Pierson and E. H. Thompson (R.A.F.), all four veterans of numerous trips, were killed. F/O A. W. Bellos and P/O R. J. Thompson escaped without injury. While the six Lancaster squadrons were busy over Ludwigshafen the eight Halifax units of No. 6 Group were bombing Mainz. Over eighty Canadian kites were included in the attacking force of about 325 bombers. Similar weather conditions were encountered. At the beginning of the attack ground markers were well concentrated, but the clouds later closed in and obscured them. A good supply of sky markers enabled the crews to complete a successful attack. Through the cloud layer the glow of incendiaries and fires was clearly visible, with several explosions adding their evidence of destruction to Mainz. The city, an important rail centre at the junction of the Rhine and Main rivers with a large inland harbour, was one of the major trans-shipment ports on the upper Rhine. Extensive engineering, railway wagon and shipbuilding works added to its economic importance. Frequently bombed in the past, Mainz suffered extensive new damage this night, particularly at each end of the city’s centre. The state railway offices, town hall, police and fire stations, law court and central post offices were among the public buildings which received a severe battering. P/O W. D. Corbett of the Alouettes won the D.F.C. on the Mainz operation for completing the mission with one engine u/s and a second threatening to pack up. On the 2nd simultaneous attacks were delivered against Wiesbaden by the Lancasters and Wanne-Eickel by the Halifaxes of No. 6 Group. The latter attack was made by a force of 290bombers, including 96 Canadian Halifaxes and seven Vancouver Lancasters. Sky markers were soon lost in the solid bank of cloud which towered over the target, but their glow remained visible and navigational checks confirmed the accuracy of the Pathfinders’ work. It was, of course, difficult to make any accurate observation of the results, although the reflection of bomb bursts and photo flashes indicated the bombing was fairly well concentrated. Several explosions, three of which were particularly large, could be distinguished, followed by a red glow which developed steadily and was visible for 60 miles. Photographic reconnaissance subsequently confirmed that moderate damage was done to the synthetic oil plant at Wanne-Eickel where a fair proportion of the bomb craters lay within the target area. Four bombers did not return, including one Canadian Halifax from the Leaside Squadron flown by F/L G. H. Thomson, F/O s H. Bloch and J. T. Robinson, WO A. M. Jones and Sgts. R. R. Vallier, W. H. Haryett and R. G. E. Silver who were just beginning their operational tour. A Thunderbird Halifax, skippered by F /O J. Talocka, was hit by heavy flak over Wanne-Eickel and crashed as the pilot attempted an emergency landing at an English base. The pilot and five of the crew, F/Os J. M. Styles and S. G. Arlotte, FSs J. A. Chisamore and A. G. Bradley and Sgt. G. Needham (R.A.F.), were killed. Only the wireless operator, WO S. E. McAllister, escaped. Wiesbaden, the second objective that night, lies a few miles east of the Rhine opposite Mainz. Noted chiefly as a health resort famous for its mineral waters, the town was a centre of first importance for the assembly or rehabilitation of troops. Some industries and railroad lines added to its significance. Sixty R.C.A.F. Lancasters formed part of the attacking force of 450 bombers which found a solid bank of cloud over the target area, with tops rising to 20,000 feet. The winds varied from those forecast with the result that nearly all the aircraft were late. When the Pathfinders dropped their markers they were soon hidden in the thick clouds and ever, the glow was scarcely visible. Deprived of the customary target marking most of the crews used navigational aids for bombing. The attack in consequence was not well concentrated, the glow of incendiaries dotting an area about fifteen miles square. Photographs later showed clusters of damage well distributed over the whole town with moderate concentrations here and there. Various industries, public buildings and utilities, including the casino, municipal gas works, main railway station and freight sheds, showed signs of damage, principally from fire. Flak opposition was not severe but over Wiesbaden, as at Wanne-Eickel, some enemy fighters were in evidence. Two of the seven missing bombers came from the Moose and Ghost Squadrons. In each case, there was only one survivor. FS W. J. McTaggart, rear gunner in the Moose Lanc, later reported that his aircraft was shot down by ack-ack just after releasing its bombs. From P/O C. M. Roche, also a rear gunner nearly at the end of his tour, there came a similar report. Just as the bomb-aimer reported “bombs away” there was a terrific explosion. Semi-conscious, Roche had only a vague memory of baling out and landing in the snow near Wiesbaden. A second Ghost bomber was lost in a crash landing near base in which two veteran members of the crew, P/Os R. A. Playter and J. A. Keating, were killed. In the two missing Lancasters F/Ls D. E. Berry and C. J. Ordin, F/O C. Walford, and P/Os F. E. Hogan, J. C. Harris (R.A.F.), and K. M. Hammond of the Ghost Squadron (all credited with 28 to 30 trips), and P/O B. W. Martin; F/Os J. A. F. McDonald and R. W. Hodgson, FSs P. F. English and R. A. Nisbet and Sgt. J. McAfee (R.A.F.) of the Moose Squadron were missing, believed killed. The next night, February 3rd, was quieter with the Vancouver Squadron the only R.C.A.F. unit engaged on operations. The target, attacked by 190 Lancasters and Mosquitos, was a benzol plant near Bottrop in Westphalia. In contrast to the previous night the skies were clear. The Pathfinders did a very accurate job; the bombing was well confined and fires, explosions and great columns of black smoke indicated a successful attack. The western section of the Rheinische Stahlwerke A.G. coking plant, in particular, was very badly damaged. Although enemy fighters swarmed over the target area and along the homeward route, all eight Vancouver Lancs returned safely with one Jerry kite to their credit. West of Bottrop, on the way home, the crew of M-Mike, captained by F/O W. G. Forsberg, D.F.C., sighted and opened fire on a Ju. 88 at 300 yards’ range. The night fighter pulled up into a stall and fell away in a curving dive with its port engine on fire. Twelve thousand feet below it exploded on the ground….”

Oxford University Press, Amen House, Toronto LONDON, EDINBURGH, GLASGOW, NEW YORK, Geoffrey Cumberlege, Publisher to the University COPYRIGHT, 1949 by OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national…/book-1944-rcaf-4-years.html

So that’s where I was shot down–on that target. I was blown out of the aircraft. The last voice I heard before we blew up was the bombardier in our aircraft saying something like–starboard two degrees, then straight. Then I heard him say “bombs gone!” The minute he said bombs gone– lights out! I don’t know how I got out of my aircraft. One moment I was behind the gun and then I wake up and I’m like a limp rag. At one o’clock in the morning, floating in the air and I hear the bombers going home. I recover and I look – all my connections to the aircraft were ripped out; my oxygen, my intercom and my electric suiting. That’s it!

I know what I had been trained to do: if the Skipper says prepare to bail out then automatically the tail gunner like me – my back is to the aircraft and the door is there – automatically I turn the whole turret to the side and then reach back to make sure the door is unlocked, eh? Then after that, he would say bailout and with my hand locked on the chute then I’d jump out. There was nothing like this, I just went from a locked-in position with my back to the aircraft and then I was completely out of the plane. I can’t explain it. Who opened the chute? I must’ve made some movement to go through the opening, which is only about six inches; the guns take up space. Everything was ripped out and I had all these wires hanging down and I’m locked into a little ball out there and I can’t explain how I was separated from that thing and everybody else killed. I’ve no idea – I try to think of how. I was locked into the turret! Then I was knocked out completely in this huge explosion. In the back of my mind, I feel as though I put my arm out to try and go right over the top of the guns – there’s a small space. There’s no way I could go out there, you know. I just don’t know how I was separated without breaking something or tearing my legs, my body and my head, without ripping myself into pieces! I still can’t explain. It’d be like you’re sitting here and somebody came up and smashed the back of your head with a baseball bat. Like they whacked you full force, you’d be out of it, you wouldn’t be able to react at all. Ya, it was very strange.

I don’t even know how much time elapsed from the time that I was blown out or even how I left the aircraft I opened my eyes and I was in my parachute. It might’ve been thirty seconds or it might’ve been a half-hour. Of course, when I say I was shot down over Wiesbaden, the wind was blowing enough; it took me about ten miles away from the target. Then my parachute was open and it was kind of doubled. I must’ve been flying through space and turning over. When I came to, my chute was like two chutes–one rope was twisted, but I was swinging, I remember, and it righted itself. I could hear the drone; our gang were all going home!

I couldn’t really see but they were on their return; the bombing had been done. With the time-lapse it could’ve been a few minutes, I really don’t know, I could never explain it. I looked down, my legs were there and my arms were there. When you release the parachute you have no control over it really. I floated down. I passed out right at first after a couple of minutes because I was above oxygen. Maybe I’m at 17,000, 18,000 feet up. Then probably around 10,000 feet, I came to.

One of the odd things I thought about when I was floating through the air was–good–I won’t have to go teach now! After my last operation, I was supposed to train new gunners. I’d make a lousy teacher! Just a couple of months before, around the 30th of December, 1944, I was sent to Manby, where there was a high-security training centre. The calibre of the machine guns that I used in the turret was being changed and it was decided I was going to be a trainer.

At about 12,000 feet I was alert enough to land. To land in a little village. I sprained my right ankle. It was a foggy night and I came down in the darkness and boom–I hit a little heavy. It didn’t bother me that much you know when you’re young eh? So I landed in a little bit of snow and cow fertilizer in the back of a barn. I just missed a church steeple; a small church. Imagine–I’d be hanging off a church. I just missed it!

It was winter, February 2, 1945, right near the end of the war; the war finished in May. One lady saw me land–everybody else was sleeping in that small town.

I didn’t know at the time that I was the only one that was captured. I didn’t know what happened to my friends!

This lady who saw me was maybe a hundred yards away–while I was sitting in the snow just reviving myself and taking stock of what I had, she said something in German. She hollered at me, but I don’t speak German. I just said–gute Nacht–I tried to fool her–I yelled–das is good (alle sind gut) or something like that to mean, all is good! I tried anyway to put her off. Then I struggled to take off my parachute but the button to open it was jammed. I had a little pen knife in my pocket that I used to cut all the ropes to get the damn thing off.

I didn’t want to walk around dragging a parachute. I remember I bundled it up – I had my Mae West on, so I got all my things on my arm and got out of the snow. I walked–I said I better get the heck out of here because this lady might report me. I walked about a hundred yards when I saw a little creek. I remember as a kid we used to read Dick Tracy; the comics–they always walked up a creek to put the dogs off track. So I said I’ll be a smart ass! It was cold! It wasn’t deep; it was about four or five inches of water. I walked up this creek, and then I said enough of this business! Then I headed up into the mountains, a small mountain really, probably like Mount Royal. It may have been a chain of mountains. I climbed and I climbed for about an hour and the snow got deeper. I remember it started off a few inches then got deeper. While I was walking I made plans, I had a compass and my scarf had a map on it so I could try and make my way back, hide out in barns along the way. I figured maybe I could grab some chickens, eat chickens as I went along, you know anything to keep me alive. Finally, I said–oh the heck with this! I was tired and beat up; I was covered in oil–on my face–from the explosion. I had my parachute and I was carrying all this junk, I didn’t want to leave anything to identify myself. So in a little opening in the woods where there were no trees I threw the parachute on the ground, then I jumped in it with my clothes on and pulled it over top of me and went to sleep. I slept till about noon; I was exhausted–all the excitement! You know it’s strange when you’re young and kind of foolish; I don’t remember being nervous or scared, everything was sort of matter of fact.

Today I’d need about four or five changes of underwear but at that time… So the first thing I thought of when I woke up, in case somebody comes looking for me I threw out all my identification and a few Pounds of money and my lion movie pass, it wasn’t very useful in the middle of nowhere in Germany. I had some candies and a couple of cigarettes left in a package.

The lady who saw me the night before, she saw me drop from the sky, I guess she went and told someone. She probably said this fellow he doesn’t belong to our gang–in a parachute–they don’t just drop in! They had dogs that tracked me down, Rottweilers, some pretty hungry-looking dogs. With the dogs were a group of home guards and a Luftwaffe Corporal in charge. They all had sten guns, small submachine guns, you know. The sun was out, it was a bright day and I could see them coming. When they got within 100 yards I put my hands up and hollered out ‘ya got me, boys!’ They were a mixture of ages, young and old, might’ve been seven or eight of them in the group. All that, looking for one tough guy, but I wasn’t armed; we didn’t carry arms. It was probably a blessing that I was caught, or I would’ve been wandering through the mountains. At some point, I might’ve even run into troops from either side and both would’ve shot first and asked questions later.

Germany’s Home Guard

1944: “Conditions inside Nazi Germany were changing. The repercussions of the 20 July bomb plot against Hitler were still playing themselves out. Public trials of men suspected of being associated with the plot demonstrated how the regime would crack down. In an increasingly paranoid atmosphere there was now even less chance that any anti-Nazi remarks might be ignored, people had to be very circumspect about what they said. The threat to Germany’s borders now seemed very real. In response the Nazis were establishing a “People’s Militia” – the Volkssturm. Conscription papers for all between 13 and 60 had already been sent out, an inaugural meeting would be held by Reichsführer SS Himmler on the 18th October – the new force would be under control of the Nazis rather than the Wehrmacht.”

From: http://ww2today.com/13-october-1944-arrested-by-the-nazis-for-undermining-moral#sthash.gynitrjc.dpuf

They brought me down to the village, paraded me along the road so the villagers could throw stones at me. Luckily I was heavily dressed, had on my electric suit, and a leather bomber jacket that I had bought in Dundee, Scotland at the St. Andrew golf course. At first, they thought I was American because the leather jacket was similar to what the Americans wore, but I took that off to show them my Canadian Air Force battle dress uniform – I had RCAF badges on my uniform. I was questioned at the town hall by a school teacher; she was very pleasant; I guess she was the only one who could speak English. All I could give her though was my name, rank and serial number. She took down that information anyway and probably turned it over to the forces or intelligence.

The Luftwaffe Corporal was intent on bringing me to interrogation, so we walked over the mountains from that little town. One night when we stopped, I slept on the floor in a little cabin; there were a couple of offices there. I remember it was a camp full of these little boys wearing uniforms with swastikas – like a Boy Scout camp, you know; camps for children. They were all little boys, ten, twelve years old; they were being trained as Nazis, eh? Hitler’s youth movement, they all had Nazi outfits on. That I think was the most unpleasant thing I’d ever seen in all that time. It wasn’t hunger or being beaten up or solitary confinement; it was the chilling site of all these young boys dressed like Nazis.

The next day the Corporal and I moved on. When we got close to Wiesbaden, which we had bombed a couple of nights before; we were met by a Captain in the Wehrmacht. He stuck a gun, a Luger, in my face; he was going to blow my head off! I was still being escorted by the same Luftwaffe Corporal (luckily); he turned his gun on the officer and said something. I imagine he said, this is my prisoner and I’m bringing him to the interrogation centre in Frankfurt. They had an argument for a while; then we finally got going. It was impressive that he argued with a superior officer, but the officer was an army man and he was an air force corporal. If that had been a superior officer in his own regiment it probably would’ve turned out differently.

We came across a group of people with pitchforks and they were going to hang me in a tree! Civilians, you know! But look at it this way – if your family had just been blown up you wouldn’t be too happy with the enemy just dropping in. I felt everything kind of a matter of fact; to me, I was kind of resigned – well, so what – it’s the end of me. The Corporal turned his gun on them, and told them – this is my prisoner! They turned away finally, they were all mad and it was no wonder! He brought me a little further and left me overnight at a jail. It was an old jail; the top part was all blown to bits but it still had some underground dungeons. I remember a couple of the guards were told by the Captain of the jail to take me downstairs. These fellas had been drinking and they had their girlfriends down there. They roughed me up a bit then they both grabbed me and threw me down a flight of stairs; about twelve stairs. When they grabbed my arms, I was asking for trouble! I hung on to them and all three of us went rolling down the stairs. They had a few drinks, thank God! They opened a cell underground in the dungeon and left me there overnight.

The next day the Corporal turned up again and brought me further on and left me with a bunch of black-shirted SS gang. They were a nasty crowd! The SS wore black shirts with the Swastika on their arms. They were like police, these guys, like a national police force. I wasn’t too happy! They scowled at me and grumbled in German. I slept there one night and then the Corporal proceeded to bring me to the interrogation centre, where I stayed for a couple of weeks. On the way I met another prisoner; he was RAF, I remember giving him my gloves because his hands were burned. These were nice leather gloves with a button on the cuff, but he needed them more than I did. He was very nervous and said he wasn’t going to talk to the Germans. He told me not to talk, no matter what they do, even if they shoot me. I don’t know why I was so calm, I told him not to worry about it, they’re not going to shoot anybody. I was trying to calm him down. We knew the end of the war was coming, but not when. It could’ve been in the spring or the summer. I was always optimistic, I don’t remember being downhearted or scared, maybe it was just because of my age. If they had shot me – I thought – what the heck! We’re the enemy and we did a lot of damage to them. I wasn’t very brave though.

The interrogation centre had solitary confinement and they’d keep you as long as they wanted to try and get information. In the waiting area, I was interviewed by a man who spoke English quite well. He was very pleasant; he offered me a Camel cigarette. The only time I smoked was when I joined the forces, I didn’t smoke before. So I took it and told him – you know the Geneva Convention, all I can give you is name, rank and number. He said okay, and he cut it short then. They put me in a little cell; it was about 8 feet x 4 feet wide with a little bunk. They’d send a man in civilian clothes around but he didn’t bother me.

He went next door and there was a young American boy in there, his whole crew I guess were captured and they were in different rooms. I heard the civilian man, a German chap – the interrogator – he said: you know – all your boys – we just want to know what station you’re on and ask a few questions. Your boys are going to be leaving tomorrow; they’re all going to a regular prison camp. It was probably Nuremberg, but we didn’t know that at the time. So he said we just want some information. The American asked if they were really going and he answered, oh ya, they’re all going; we don’t need them anymore. You’re going to be the only one that’s staying here.

I got into a little trouble there – I started singing ‘bullshit is all the band can play!’ I knocked on the wall while I was singing. They sent a guard around, funny thing, I’m laughing about it now. The guard yelled ‘shut up!’ in German. I knew what he was saying though, but I didn’t hear the American talking anymore.

They called me out periodically. One time I was sitting at a little table and there was a light fixture above the table. The interrogator was very pleasant and he spoke perfect English – he was asking for information. He’s not really going to waste his time. He left a big book in front of me, and then a sergeant came to the door and asked to see him, so he stepped out for a while.

Being a nosy guy and also being conscious that they weren’t stupid, I figured the room was probably wired. I’m sure that in the fixture above me there was a camera, you know.

When he left the room this book was right there in front of me. It said something about information. I started turning the pages, turning each page at the same speed trying to be casual about it. A number of the pages I looked at really shocked me, though I didn’t want to show it. My head was down in case there was a camera. They knew more about my own squadron than I knew about it! I think they probably get people who are on medication, people who are badly injured or something and of course, they’ll talk! If someone’s full of medication of some sort and they talk, it’s not their fault. I was amazed! Then I just closed the book, in case they were watching. My gosh, they were asking me for information about radar and things. I don’t know anything, I’m not a navigator! Radar! These are the things they always wanted to know about. I knew my job as a rear gunner and that’s all I had time for.

In the interrogation center, in my tiny room that was just big enough to fit me and a cot, there was a little knob on the door. I decided to take the wiring out of my electric suit; I had no more use for it, no place to plug it in. With the little knob on the door handle; I played ringers just to pass the time. I made little rings with the wires and threw them onto the handle and I won every time! I beat everybody I played with! (There was no one else in the room) So they kept me for about another week and they kept going back over the routine, you know, name, rank and the rest. Then finally they threw me out.

They brought me to a small camp. I don’t know what it was called or where it was. At this camp, I bumped into a fellow from the west end of Montreal. He had a bad leg injury, his leg was broken. He landed in France, or crashed in France; the Germans had controlled that part of France. Some people on a farm took him in, got him out of his uniform and put him in overalls to look like a French workman. Then gangrene set in, I think, and they were afraid he’d lose his leg. So they thought it was advisable to put him back in his uniform and turn him over to the Germans. Then he’d get medication to save the leg, eh, ‘cause that’s one thing at that point; they would look after an injury. So he had all the treatment and was in this small camp that I was in while we were on our way to Nuremberg. Later it ended up I carried him for a while when we were on our forced march out of Nuremberg.

I don’t remember much about the transportation from one place to another with the Corporal, on our way to Nuremberg. It took us a while to get there, a week or two. At one point we were on a public tram, there were people sitting down all around and of course, they were all looking at us. The corporal had a gun but he wasn’t too obvious about it. We were instructed before, maybe about halfway through my operations – when it looked pretty darn good for our side – that if we were captured not to be too smart aleck about it. Just surrender and go with them, don’t fight them. Earlier in the war, I carried a .38. They stopped that, I had no gun when I was shot down in the end, in other words for self-defence, you know.

The Corporal and I got off the tram and then we had to walk along a crowded street. A man nudged me and quietly said in English something like, keep your chin up, it’s going to be over soon! I guess it was one of our spies or one of the allied armies who was in the city in advance of the troops; he was someone who spoke perfect English. I had a guard behind me with a gun; we were separated by a yard or two and this fellow is telling me it’ll be over soon! I didn’t even have a chance to look, he just disappeared into the crowd, you know. I don’t know who it was, he was in civilian dress, not in a uniform, and he spoke perfect English. He saw me as a prisoner with a guard at my back, and then he just got mixed up with the crowd and vanished! I don’t know if the Corporal even noticed or would be bothered. I was very fortunate that this German fellow was doing his job in a disciplined manner. If that happened in Canada or the United States, our people, I don’t know if they’re all that disciplined. German people are disciplined; I would’ve been long gone otherwise.

It breaks my heart that I never saw the Corporal after the war. He saved my life. I didn’t know how to find him after the war.

The other time I remember travelling with the corporal was when we hitched a ride on a truck. It was transporting other prisoners of war. At one point we all had to jump out into a ditch. A fighter plane came down with a machine gun because the truck wasn’t marked. Luckily, we weren’t all killed although there were injuries. Maybe the fellow realized that there were prisoners of war. There was always a danger if your transportation wasn’t marked, like with the Red Cross symbol that your own people may come down shooting.

After the truck, the corporal dropped me off at a big hospital in Wiesbaden for the night. It was a recovery place for German soldiers. It must’ve been about five or six stories high, and they put me in a cell on the fifth floor. That night the alarm went off for a bombing raid by our people. They came to the cell and said, ‘rouse, rouse! ’ It meant get up, eh. They opened the gate and I said, look I’ll stay here, I’m okay. They said no way in German and forced me to go down into a bomb shelter in the basement of the hospital. I was surrounded by, I don’t know, maybe a few hundred wounded German soldiers! I thought, holy man, here I am the enemy, and the enemy is bombing the place, and I’m down here with all these Germans. Of course, they’re grabbing me looking for souvenirs and stuff. I’m just sitting there! You can’t argue with four hundred people. That wasn’t a very pleasant experience but it just lasted for, I guess, half the night or something, then I went back up to the cell.

Wiesbaden means ‘meadow bath’ and was a popular spa area for the rich for centuries. At one time there were twenty-seven hot springs but now there are only fifteen. Wiesbaden was on the allied bombing list from 1940-1945 and had, in that period, sixty-six days of bombing. Hitler’s youth were children, who had no choice in the matter but were taught to hate, to fight, and to kill. They had a long succession of previous German youth groups to follow as models. The industrial, materialistic world of the early nineteen-hundreds prompted youth to break free from their families and society to become romantic wanderers. By the time World War 1 started the youth groups felt that war would cleanse society of its fascination with industry. In 1914 thousands of youth belonging to a group named Wandervogel swarmed the British in battle. Over 1,200 youth, which was more than half of the group, did not survive. The remainder dwindled to almost nothing. The dead children became national heroes. Then the youth groups turned into anti-democratic political activists. Some were communist groups, while others were already part of the Hitler Youth in the early years of Hitler’s reign. When Hitler was exploiting the unstable Weimar regime, the youth groups became unstable looking for a common cause. Former, older, youth league members tried to become leaders of the younger ones causing chaos in the leagues. Hitler and his party seized the moment becoming sympathetic to the youth to bring them into the fold. They were promised a place in the dream of a thousand-year Reich. On January 30, 1933, Hitler became the German Chancellor. At the same time, the separate youth groups were absorbed into the Hitler youth league, one hundred thousand strong. By the end of 1936, there was 5.4 million Hitler youth aged ten to eighteen years old. In a further attempt to wipe out all other remaining youth groups, their leaders were sent to concentration camps. Hitler’s youth were responsible for street fighting and bullying others, they destroyed synagogues, beat up Jews and Catholic priests, and publicly humiliated Jewish women.

The Boy Scouts who were one of the last hold outs and had been left alone for a long time were attacked; beat up by gangs of youngsters. The Gestapo then clamped down on any other stray youth group. Hitler wanted unity of youth so no religious groups, communists or any other political groups were allowed. As the war progressed, orphans were brought to the camps to be taken care of. The children had a uniform to wear, black shorts or pants and a khaki shirt for the boys and a blue skirt and white blouse for the girls. Boxing became a favourite sport for the boys since it was a favourite of Hitler. The children also went on long hikes, played war games and there was instruction in the use of firearms for the boys. The younger boys started out with air guns and the older boys used rifles. The older boys were also allowed to carry handguns. Some children’s camps became specialized. Those interested in flying were trained with gliders and later welcomed into the Luftwaffe. Some children were in sailing instruction; others learned all about cars and motorcycles, horseback riding, communications, phones and Morse code. There were camps for children who were musically inclined. The only music allowed was German, military music or songs about the Führer. The main objective of all of the camps was for war training. Around the time that Charles was captured, in 1945, children as young as ten were being put on the front lines with tragic results. The war training could not prepare them for the horrific reality of battle.

Camp training for girls was not as rigorous as it was for boys. Girls were expected to learn all the skills a good German wife and mother would need. In 1938 the leader of the youth league, Schirach and Hermann Goring decreed that all teenage girls had to have at least one year of work as a farm labourer or household maid. This unpaid child labour helped fill a labour void. By 1941 all unmarried women were ordered to work in munitions factories and hospitals, also as telephone operators and stenographers. For those Germans who had re-settled in Germany from Poland, the young Hitler women had to teach them proper German and Nazi standards for bringing up children. Girls also had to collect medicinal herbs or supervise younger camp children.

As time went on and more men were part of the war machine, including youth who were old enough to join the army, girls and young women assumed jobs like tram conductor, postal worker, and work in police and fire stations. They also had to operate soup kitchens for the bombed-out homeless population. The SS also found a need for young women to work in concentration camps. Not all became cruel, and some were allowed to leave, but one Hitler youth, Irma Grese, revelled in cruelty. At the age of twenty-three, she was hanged as a judgement in the Nuremberg trials. All the children in Hitler’s youth league were being used. Young, underage girls were picked up by soldiers and Nazi leaders as well. Girls were taught that their only function in life was to bear children, to populate the new German order. Legalities like protecting these young girls were unimportant. Early on in the quest for a homogeneous Hitler youth, there were some teens who decided to defy orders to join up. They were a small group from wealthy families and the teens liked to collect American jazz music and party. In other words, they were like teenagers of every generation. A special concentration camp was created for wayward youth with this group as the first prisoners; put there to teach them a lesson.