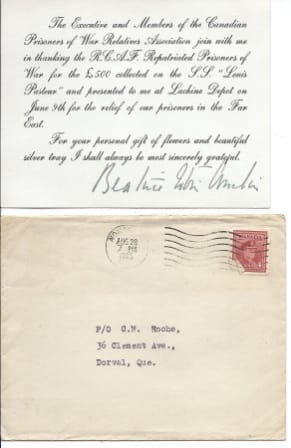

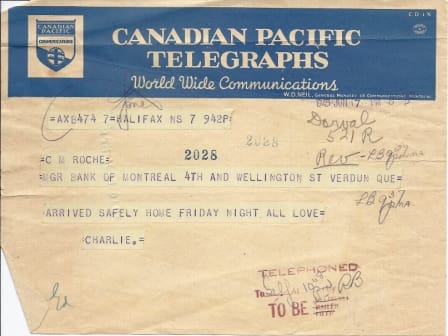

I was shipped home on the Louis Pasteur. The ship was filled with RCAF ex-prisoners of war. I do remember that money was collected to donate to the War Relatives Association.

The poor ship was beaten up and wasn’t very comfortable. We slept in hammocks and on wooden boards. At least it got us safely to Halifax.

This lady Beatrice had a son who was a year or two older than me. He had gone to Loyola College. He was a POW. She was president of an organization that sent packages to POWs. She did a lot of work for us. So in honour of that, we all kicked in a number of dollars.

When we arrived in Montreal we gathered at the old Manning Depot in Lachine, back to where I started out. My mother wasn’t there because she wasn’t well enough to go that day, but my father and sister were there. There were bands playing and cheering crowds! The Americans; when they got home had an even bigger reception. The British though, when they got home, they had to walk or take a bus or train to get back to their families. Some of them had been away for five years, then they’d just show up at home with no advanced warning or fanfare. In London, it must’ve been awful for the returning soldiers. Their homes would’ve been flattened and their families moved or dead.

We had a choice to stay in the armed forces after the war. They asked us if we were interested in going to Japan. I thought, sure, I said yes, I’d go because the war was still going on after it finished in Europe.

Then they came back and told me no, you’re not allowed to go because you were a prisoner of war and they don’t allow ex-prisoners to go off and fight again. they figured you’re lucky enough to survive once.

I came back from the war in the spring, eh – May or June. The war was over and I had the whole summer off. The air force paid me – I was still in the forces till September. So June, July and August I would bicycle to the Grovefield Golf Course in Lachine, where I had a free membership. All summer, every couple of days I’d paddle my brother’s canoe across to Chateauguay, just to stay in shape. Just to get back some weight. I’d dropped down to 140 pounds; I was skinny. But then I started playing hockey again the next winter.

When I got home I had some correspondence inquiring about the crew from my last flight. I didn’t answer, I couldn’t face up to it, so my father answered the letters. I went to Ottawa and met my skipper’s wife. And I went to Toronto and met my wireless operator’s wife.

The letter above is from Mrs. George Hammond, I think her name was Edna and she was the mother of Pilot Officer Kenneth Hammond who died in the ghost flight. It’s a very sad letter, she’s hoping that Charlie can give her some information about her son. Mrs. Hammond thought that since Charlie survived then maybe Kenneth did too and was possibly a POW as well. I tried searching for any Hammond that might be related – to ask them if they’d mind if I put her letter out there. But, people move, get married, so I wasn’t successful.

The letter is dated June 10, 1945, so I guess at that point the RCAF hadn’t found the remains of the plane and crew. Charlie said they were eventually found. No body was found for Kenneth Hammond so he is listed among the RCAF war dead on a U.K. Memorial.

Doug Barry was the pilot (the skipper) – he was a decorated pilot – he was given the Air Force Cross. Doug Barry’s wife was a nice lady, it was just a short visit. The other lady I visited was in Toronto. This woman was a patient of my uncle in Toronto, who was a doctor. She talked to her doctor about her husband who was lost in the air force, and that only one person survived when the plane blew up. My uncle told her my story about the last flight. It turned out her husband was in the same crew, on the same flight!

There was one fellow from Vancouver. I have his watch; he gave it to me when he got a new one. I still have the watch.

There was a burial for two of my crew. Unfortunately, they couldn’t find the others.

In September I went back to Imperial Oil – when I was 17, I had worked as a mail boy before I joined and went overseas. When I came back they gave me a crummy job in the traffic department. It was a big office with an accountant behind glass in one corner and a manager, McCarthy at the other corner. The chief accountant was there because it was the office for all the accounting people in Imperial Oil and shipping and all that crap. I was sitting down in the back– I was at a desk and they gave me a book and in pencil, I had to mark the numbers of freight cars and stuff. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. They just said you go across and you copy from this – it was a really crummy job, but what the hell it put money in my pocket. I lasted oh, about under a year with them. That year I played hockey during the winter. I played in Lachine with the Lachine Rapids in the senior provincial hockey league. They paid me about fifty bucks a week. They had some fellows from that team go into the pros; like the Canadians.

There were teams like Joliette, they probably don’t exist anymore in the league. Before I went overseas I was with the Junior Royals. I left the Lachine Rapid junior team in 1942 and went with the Montreal Junior Royals, Lorne White was the coach. They had a good team – the best junior team around – there was also a junior Canadians team. In 1942 they came into the dressing room and said – has anybody joined the forces? I had just joined the air force – that was my ending with Junior Royals.

Before the war, I also worked at the Eaton Co in the sporting goods department. And I worked for my mother’s first cousin – Tom Trihy – he was an agent for Holden and Co. from Ottawa. Holden sold camping equipment, mainly for people up north in the pulp and paper industry. I sold sporting goods for them. I didn’t speak a word of French and I remember he dropped me off on St. Hubert street and he said cover all those drug stores, I didn’t have a car and I went knocking at doors. I didn’t sell anything – the last call I made was a sporting goods store and the fellow bought a couple of dozen jockstraps. I stayed with that company for a while. I remember Bourgie in Lachine, the funeral parlour, the two Bourgie boys were both hockey players – they were good, one played for the New York Rovers and they had played also on the Lachine team with me after one of them came back from New York. They opened up a sporting goods store in Lachine, so I furnished them with stuff that I was selling to equip the store.

In the 40’s I really monkeyed around, but when it got to 1950 I worked for an automobile guy on Cote de Liesse road called Auto Plane, which was in the late forties. I was at Auto Plane and the vice president there, George Doyle – brought me in as the first salesman they had. They owned the land behind where the Hilton Hotel is now. And they were going to make a racetrack for cars nearby, I would’ve been in on the beginning but before that happened; the owner and his whole family were killed in a plane crash coming back from Florida and everything changed. So after that, I was out of a job for a while, but I was still living at home. I had a little Ford Meteor car, it was double financed with IAC and Canadian Acceptance Corporation. I had worked for a while with Canadian Acceptance as a repo man; that was before the car business.

During the late 40’s I was a repo man. I used to repossess cars. My jobs mostly came from connections from the golf course. Anyone I knew who was into sports used their connections with sports to find jobs. Golf was one of the best because all of the executives, presidents and so on played golf. When I was nine years old I carried bags for spending money. I was a scratch player, I was shooting in the seventies when I was about thirteen, or fourteen. I remember winning at the Elmridge golf course.

In ‘49 I went down and played hockey in Amherst Nova Scotia. The team got into trouble, cause they brought me down there, I was getting about two hundred bucks a week, that was big money in those days. I had free room and board, the whole deal. They entered me in the St Francis Xavier University; they paid for that – that was after January in 1949. I think I was enrolled in the University for basket weaving or something – I never actually went to school there. They do that in the States for football players. I never got any degree though, nor do I get to be an alumnus. I got my degree overseas when I was in the war.

I think being confined in the POW camp and close to Frankfurt where I was put into a dungeon by the guys for a while, down underneath, where the place had been bombed out. And the hospital for sick German soldiers they put me in a cell there for a while too. So especially after that I always wanted to be outside so every job I had, selling or collecting – they were always jobs on the road, always in a car driving. Even with the Sun Oil Company where I worked for about 10 years, 1950-1958. I left them when they finished their expansion program on service stations. I was buying land for service stations in eastern Quebec, Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Shawinigan, Grand Mère, Trois-Rivières, and Montreal. I was never too far away, but occasionally I stayed in hotels.

In 1958 I went on a trip to the States with my mother. That was just before I got married. That’s after I left Sun Oil. We drove all the way through, and I visited some of the vets down in the states, from the POW camp, I didn’t get to see Glesener, he was transferred out to the Pacific coast, but the big guy who was a professor in Blacksburg, Virginia – Jim Ashley; big Jim. Then I continued on to Florida and I went to Cuba from there. We flew to Cuba then got back to the car and I had my golf clubs, and we followed the coast right up to New Orleans. We stayed in New Orleans for a little while and then we went on to Texas and we visited the two waterfront cities in Texas. We went to Monterrey, Mexico, I’d play golf and meet some friends from the war. I was going to go on to California because my dad’s cousin was the mayor of Los Angeles, I never met him but I read articles about him but when I phoned home they said he had passed away. So instead of heading further west, from Mexico I headed into Oklahoma and came back on Route 66 right to Chicago where I met my uncle Norbert, the doctor. We had dinner with him and then we came back to Montreal. It did my mother some good, she needed a change. It was ten years since my brother died, but still, it seemed to help her. She’s the only one that could take the time to go with me. I was going to go back into the oil business, buying land for McCall, Frontenac.

One day I saw Red Storey, the old referee in the national hockey league and former Argonauts footballer who I knew very well from playing hockey. He hollered across the street, on Sherbrooke Street; hey, what’s going on? I said I was just back from the south and that I had been asked to join McCall Frontenac as manager of their real estate department. So he asked if I liked the idea. I said, well, I did it for ten years. He said – we have an opening in the liquor business. He was with Thomas Adams Distillery. Red Story became a public speaker, he was quite a character, a very good guest speaker – they used him all over the place and he used to get paid pretty good for that. I brought him out to the golf course, Summerlea as a guest speaker at our closing dinner way back in the ’60s. I go back so many darn years now, I forget!

I was with Thomas Adams Distillery, which was owned by the Bronfman family, till they sold it. So I worked for Thomas Adams for a couple of years. With the distillery, I covered the Eastern Townships, all the liquor stores, and hotels, and clubs. I’d make a circuit, down through Waterloo, Magog, Cowansville, right to Sherbrooke. That was fun, it was interesting. Other trips were further up north in Ontario to the lake districts, and Toronto, we’d go to golf tournaments. It was good for me ‘cause I didn’t want to go to an office. Sitting in the tail end of an airplane never really got me anywhere, so when someone offered me an administrative job for a paint company, I told him I can barely administrate the small things I have to do. It’s not like I had an education because I was too busy fighting in the war.

I went back to Germany for work, a fellow with KLM invited me to go over and visit all the Olympic sites as a promotion with some skiers or ski instructors so we started off in Amsterdam and they treated us great – it was a good trip for me and then we went on to Dusseldorf. Dusseldorf was a city that I had bombed during the war. Then for that trip, we went on to Austria, Switzerland and northern Italy.

I was married in ’58 and we moved to Florida for two years.

I lived and worked in Florida at the big juice company in Dade City ’cause my friend from Montreal was the General Manager of Sales for the company; Pascal Packing in Dade City. When I got down there some of the management frowned on it that a Canadian would take a southerner’s job and it was embarrassing for him so I said no. But I met the owner of the Publix Stores – and that was a big outlet – there were hundreds of stores – so in conversation I said I’m looking for work – I want to stay down here in the south for a while. He said well we’re opening up a new store in Polly Hill, it’s part of Daytona Beach. He said they have management there but they need people like a checker – so I said anything, you know, what the heck – they gave me a pretty good deal, but of course he had control since he was the owner. One of them had a house in Lakeland, where I was renting a house that he offered me. So I was a checker at a big store for all the goods coming in. It was great, it worked out.

They were good people, I got to know all the gang coming in. It was interesting; I’d never been in the food business before so it was an experience you know. Then I had enough of that. I had a pretty good job prior to that in Montreal with Sun Oil as a district manager covering all the east end of Montreal and the towns outside. So Lise and I packed up and went back to Montreal and that’s when I went to work for McCall Frontenac.

At a certain age, nineteen or twenty there was a call-up to join. If you weren’t healthy you didn’t have to join or if you were in university-they’d say, well you have to have an education. There were a lot of people who went to university then-a lot of professionals! There may have been some favouritism as far as what you did in the forces. I knew of some professional hockey players – in our squadron we had Milt Schmidt; one of the best hockey players at that time in the Boston Bruins. The three German boys, that’s what they were called, Bauer, Schmidt and Dumart. They were Canadians from Kitchener and Waterloo. They played in the Air Force hockey team. In the Ghost Squadron, Schmidt was the physical instructor but he was a Flying Officer.

I was average, very average, but we had guys with university education. Not all of them got commissions but some of them were excellent students, where I was average. The ones who went into navigation had to have high marks. We took Morse code at Queens University in Kingston, and a little bit of navigation. Navigation was a tough course. We had a clever chap from B.C., Karl something, gee I forget his name, isn’t that awful! Karl was a quiet, serious man; he didn’t mix with us on the squadron-maybe he mixed with the officers. He was a Flight Lieutenant, brilliant man, a very sharp navigator. We were fortunate having the Royal Canadian Air Force. We had very sharp navigational people and good pilots too-they had to be good! We lost so many! I lost five crews!

It’s unfortunate, but I don’t remember the Luftwaffe Corporal’s name. I don’t remember if he even told me his name. We walked for miles and miles together.

Among the souvenirs I have is a beer mug from Moosburg, and a German helmet. I had a good leather jacket that I bought in Dundee, Scotland when I was on leave and went to St. Andrews to play golf. The jacket was great for cold days. It looked like an American aviator’s bomber jacket.

The German helmet is heavy. We wore a helmet too, especially on operations. Darn! I don’t think I have any pictures of myself in gear! I had flying boots that had a button that you clicked in, and the electric suiting had wires running through it. It was only the tail gunner that wore the electric suit. I don’t remember what the mid-upper gunner wore. I don’t think it was warm inside where he was but at least he had shelter from the wind and cold air. In the tail section, there was a cut (like a window) for the machine guns, so I was exposed to the cold air. I had to wear an oxygen mask.

Imagine – I talk a lot, that’s why I was good in sales but I was all by myself in the back of the plane, and my face would freeze up so I could hardly talk anyway. IODE (Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire) would send us hand-knitted balaclavas – I wore mine under my helmet to keep my face warm. We appreciated those things, the crew who were up-front, inside, didn’t need them during trips, but I sure wore mine a lot.

I brought back my flying boots, but my boys threw them out. They were the old boots I used in training, not the official ones that I had in operations. They had changed to equipment by the time I went overseas. The Mae West vest had a whistle in case we landed in the water, but, for some reason, our vests never had the whistle. The vest is inflatable and if you’re in the water you could alert somebody with the whistle because they might not see you with the waves. My brother may have used that when they landed in the water. They were in the North Sea; I don’t know how they survived. Norbert said he couldn’t feel his legs after a short time in the cold water. Imagine! The North Sea! I don’t know how he and his crew survived. My God, no one could last more than a couple of minutes in that water! Luckily a fishing boat found them and plucked them from the water.

I received a funny little pin in the shape of a caterpillar; it’s given to anyone who’s been saved by a parachute. I automatically became a member of the Parachute Club. They met once in a while after the war, but I was never interested in going to any of the get-togethers.

Letter to Charlie from the owner of the Irvin Parachute Company

Caterpillar Club: a club for those who had survived by jumping out of their aircraft and using their parachutes. The club pin was a small caterpillar (representing the insect that made silk for the parachutes) and was given by the maker of parachutes.

Leslie Irving invented the parachute in 1919. In WWI German pilots carried a parachute in a canister. The British and the Americans thought that the parachute was too dangerous to use; expecting that human error would cause the parachute lines to become snarled in the plane. The parachute saved about 100,000 lives, most of them in WWII. The Caterpillar Club was for airmen who could prove that a parachute saved their life. A parachute manufacturer, the Irvin Company, started awarding pins in 1922. The pin was awarded to honour Mr. Irvin and his invention and the airmen who were saved. Charles wore a ‘seat pack parachute’; he had to be able to sit on the parachute because there wasn’t much room in the turret.

A WWII historian who belongs to the Canadian Aviation Historical Society, Ottawa, said that there’s no way Charles would’ve been wearing his parachute during a flight. Beware of historians! According to Charles, who was there, the mid-upper gunner kept his parachute close by to grab it in an emergency. The rear-gunner had to lock himself into the turret way at the tail end of the plane. I always think of it as being inside a tin can, not easy to just jump out of into the body of the plane and put on a parachute. It made more sense to wear the parachute harness and sit on the parachute.

Charles also insists that the ‘bomb-aimer’, was called the ‘bombardier’ by Canadians. The British used the term ‘bomb-aimer’, and perhaps the Americans as well. A British historian was sure that it was the Americans who used the term, ‘bombardier’, not the Canadians. I’ve noticed though, reading through so many books and websites that bombardier was often the popular word for bomb-aimer when a Canadian was remembering their time in the R.C.A.F. The official R.C.A.F. accounts all use the terms that the British R.A.F. used.

‘PathFinder’ is another expression that differs. I often see Canadians writing the two words as one, ‘Pathfinder’, but the R.A.F. always separates the words. This is all just being picky, I know, but if anyone does research on anything in this book then the differences in terminology will show up.

It helps to be young and stupid; it was the only way I got through the war and adjusted to being home again. The four years of the war I just forgot about them, I didn’t want to talk about it. But now it’s kind of funny that’s all I want to talk about. I never told anybody where I was or what happened except my immediate family. When I got back all I was looking forward to was getting back to sports. I love sports. I got that from my father who was a star in hockey in an amateur world cup hockey championship. He was an all-around athlete. I inherited some of that.

It’s such a long time ago. I never really went over the whole thing–except in my nightmares. I had plenty of nightmares because I eventually lost five crews. I swear five of them were lost–all dead! It makes me wonder deep inside – why should I be so lucky, you know?

30 bombing

operations were a

tour of duty