I had to spend a lot of time developing night vision. We had to be able to recognize planes on a screen in a dark room – they’d be very vague, eh? You’d spend hours training like that. Another course we took was aircraft recognition. We’d take it in daylight and we’d take it in the dark; to recognize what kind of plane was coming in – if it was one of our own or the others. It was mostly the others. We’d go in escorted by fighters so we knew it was a fighter plane; we knew the Messerchmitt when we saw one. The Messerschmitt was the biggest of the German fighters; they had a number of fighters.

At ground school, we’d shoot at drones dragged by another small plane, antiquated equipment! At the same time, I had to wear a helmet, hooked up with earphones.

We were taught to go in the pitch-black night in our bombers. We very seldom fought fighters – if we saw a fighter we were taught to do evasive action. If I fired every time I saw a fighter somewhere in the sky we’d give away our position and become tracer bullets, eh? It lights up – so if you go and shoot a fighter, another fighter might be up above you and see you bullets; in the dark, he’d know where you were. Our practice was – the tail gunner or mid-upper gunner – if we spotted a fighter coming in and they got to a certain range, I forget the exact range we’d have our little range finder; we’d tell the skipper to dive to starboard or port; he’d dip that big wing. We’d drop the wings and dive, evasive action. You couldn’t do that I don’t think on a B17, but our bombers – zoom! If the fighter was coming too fast we would move down, he’d shoot, but we’d be gone already. He’d be looking for somebody else to shoot down because we’d be gone. So that was what they called evasive action. My gosh! I haven’t used those terms in fifty or sixty years!

U.K. historian, Rob Davis found a good description of the R.A.F. evasive action in more detail:

“The .303 inch (7.9mm) calibre machine guns of the R.A.F. air-gunners were outgunned by the 20mm and 30mm cannon carried by the Luftwaffe – but the R.A.F. air-gunners would not open fire unless attacked by a night-fighter; their guns were defensive. Although the .303’s rate of fire was 12 rounds per second, and its effective range reckoned to be 400 yards, at night if within visible range, the night-fighters were also within range of the .303s.

Mid-upper and rear-gunners were isolated from their crewmates except via intercom and had to stay alert for long periods in subzero temperatures. Their fields of fire overlapped somewhat; the mid-upper could rotate through 360 degrees. Helped to some extent by the Taylor combined electrically-heated suit and Mae West lifejacket, as well as heated mittens and gloves, their alertness was vital. They could call for a corkscrew (violent evasive action) at a moment’s notice. The trick was to take evasive action inside the attacking curve of the fighter, forcing him to steepen his turn in order to be able to shoot into the space where the bomber was expected to be by the time the bullets and shells arrived. The corkscrew manoeuvre was so described because when viewed from directly astern, the pattern created by the bomber was corkscrew-shaped. Dive port, climb port, roll, dive starboard, climb starboard, roll…and good air-gunners, knowing what was happening next, could fire into the space where they expected the night-fighter to be.

Few night fighter crews persevered with an attack after the bomber had spotted them, and fewer still night fighter pilots had the skill to stay with a corkscrewing bomber and shoot it down as they danced together. A determined and experienced bomber pilot could make the evasive manoeuvre so violent that rivets popped out of the aircraft. Aircraft were actually only borrowed by the aircrew; the aeroplane “belonged” to its ground crew”.”

Quote from: Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command 1939-1945, viewed Feb. 2015

I don’t remember much about travelling around to the different training units in Canada. I suppose we travelled by train. No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery School in Manitoba was the last training centre I went to. From there we went on leave to spend time with our families; to say goodbye before going overseas, to war.

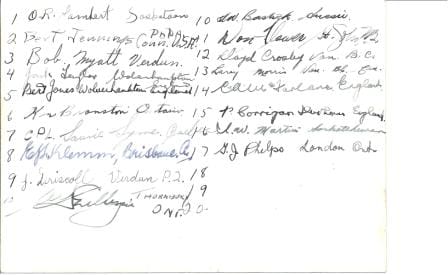

17, 1943. Charles wasn’t in this group, but they were training at the same time. Trainees wore a white shield in their caps.

Charles is bottom row, far left

When they finally sent me overseas; I was first shipped to Halifax. We arrived in Halifax on a dark night and under the cover of darkness they put us on a train. Everyone thought – what the heck is going on here? We expected to get on a ship. By train they sent us to Camp Myles Standish on the American coast, I believe it was in Massachusetts, I’m not too sure. We stayed overnight, and the next day we were moved to New York where they put us on the Queen Mary!

So here we were on the Queen Mary and there were other ships as well, the Normandie, (later named the USS Lafayette) and the RMS Queen Elizabeth, full of troops. Those were three of the biggest touring ships. Glamorous! Luxurious cabins, huge dining rooms – here we were! The cabins were built for two people; we piled in fourteen or fifteen guys. When they found out I was a gunner, I still have a badge – a white badge; I was able to go upstairs because they put me in charge of a big sixteen-pounder – a great big gun to fend off the U-Boats.

They (the cruise ships) zigzagged – they took about ten days normally and they zigzagged. They’re too fast for submarines. The U-Boats liked to pick on the slow freighters.

We had thirteen thousand on the Queen Mary if I recall. When we got to the other side we were short four or five fellows. The Americans had crap games running. In the crap games, when they didn’t like someone they threw him overboard. Ya, we were four or five short, I guess out of thirteen thousand that’s not bad! The fellows that were lost; they weren’t too happy. The navy and the merchant marine were escorting and protecting us; they had to pick up the lost fellows.

Charlie didn’t leave for oversees from Halifax probably because the city and the port were already full to capacity.

I lived in Victoria, B.C. in the 1980s and it was a stop for American warships. The downtown area would suddenly be packed with American sailors. They did the local economy some good but it was difficult to get into restaurants, stores and bars, sailors were everywhere! That gives me an idea of what Halifax was like during the war, except that the port was full and the city was inundated with troops waiting to go overseas. Instead of seeing it as a difficult time the people who lived there did their best to be friendly and helpful.

The CBC has a very good short doc on Halifax during the war. CBC Player, Dancing Was My Duty

The cruise ships, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth had been refitted to carry troops but were still quite glamorous as troop carriers.

The French cruise ship, Normandie, had been seized by the U.S. when it docked in New York on September 3, 1939. It’s unclear if it was ever used as a troop carrier. Renamed, the USS Lafayette, the U.S. were in the process of converting it to a carrier. On February 9, 1942, it caught fire and turned on its side.

The ship to Great Britain was packed stem to stern with members of most branches of the armed forces, Canadian and American.

When the ship docked at Bournemouth, which was the central depot for arrivals; the various personnel were sent off to their new bases. Charlie ended up at an airbase in Yorkshire in the RCAF’s 427 Lion Squadron.

According to Pierre Berton’s “Marching as to War – Canada’s Turbulent Years”, Prime Minister Mackenzie King wanted the RCAF to have our own squadrons instead of getting lost among the RAF. There were a large number of Canadians fighting the war in all branches of the forces from the onset. Yet, they were largely unsung heroes, far from home. The RAF, along with the British Navy and Army had a long history of career officers from the upper classes who had been less than keen on mingling with colonials. History did repeat itself. By the Second World War, it was often difficult to distinguish just who the enemy was when the British seemed more focused on putting the Canadians in their place instead of fighting in the real war.

The Royal Canadian Air Force was reshaped after much discussion between politicians. The RCAF was already in Great Britain but it became more cohesive in 1943 as the No. 6 Group; twelve of which were bomber squadrons based in England. There were some success stories of Canadians who stayed in the British Royal Air Force throughout the war, like Charlie’s brother Norbert.

When I was in Britain, as part of my training, I took a British Commando course. The course was in Sherwood Forest. It struck me because when I was a youngster it was Robin Hood, Friar Tuck and the boys, and here we were! If I recall it was near Ossington, you see it comes back! Commando training was about how to survive; I really liked that course! I often think I should’ve been in the army instead of sitting at the back end of a plane.

During the course, they taught us how to crawl on the ground as soldiers do. I found it easy, anyone into sports had already done that one in sports training, but some guys found it difficult. We also had to learn how to sneak up on someone and use wire around the neck as a garrotte. There was also grenade training; we already had weapons training. Commandos and spies had to learn a lot more than that, like shooting from the hip or shoulder, placing bombs to blow up bridges, stalking, camouflage; probably with burnt cork rubbed onto the face. They also had boxing and unarmed fighting, but we had already covered that. In Manitoba we had a big guy who trained us boxing and self-defence; I think he was a football player, he was huge!

We didn’t have to do navigation, we were already taught that. At St. Jean, Quebec, we had to be able to recognize lakes and streams from the air for visual navigation. At Kingston, we were taught star navigation. I did carry a compass, which I kept in my boot, it was supposed to be carried in an upper pocket. In 1945, I lost my compass; it must’ve fallen out of my boot when I was upside down in the air. I wore a scarf map but don’t remember ever using it.

Part of the survival course was to learn how to get back to base. They dropped us off somewhere in England, in the Midlands, about thirty miles away and told us to make our way back. The idea was to travel through wooded areas and live by our wits. The citizens of the towns along the way were told to look out for us. They were advised not to help us and to report us if we were seen. I was with my friend Johnny Williamson. He looked like a football player. I would’ve liked to be his size, since I played a lot of sports, but I was a skinny, wiry guy. Johnny had wide shoulders and looked a lot like Clark Gable. Actually, Clark Gable was on another squadron nearby.

Johnny didn’t like exercise and wasn’t into sports. So as soon as it was dark we headed into the nearest town. Nobody noticed us. We found a pool hall that was closed; so we broke in and went to sleep on a couple of the pool tables. Some men came in, in the middle of the night and woke us up. They told us we were caught so we had to give them our names and numbers. So I said I was Sgt. Joe Smith and my number was R20719. Big John was sound asleep on the other table. They woke him up, though I realized he must’ve heard the whole thing because he gave a fake name and number as well.

They let us go, so we made our way to the railway station. We didn’t have any tickets but we got on the train anyway; I don’t know how we got away with it. We went for a number of miles back to the camp. When we got off there was a man with a truck who gave us a lift right to the camp gates. We hardly had to walk at all; maybe a mile in between. It was supposed to be about survival. We were told we were the first ones back.

So here we were sitting on our cots waiting for the rest of them – they showed up a couple of days later. Most of the guys had gone through the woods, got lost, and were probably starving. I thought – what the hell – Johnny is a buddy of mine, he doesn’t like exercise, so I couldn’t just leave him alone; he’d probably get lost.

Camp X in Ontario taught spies the same techniques that commandos had to know. Among other assignments these spies or operatives often had to go to Europe to rescue crews from downed allied planes and bring them back to safety; usually with the aid of the French underground operatives. A really good book about Camp X and spies and operatives in WWII is: “Camp X: Canada’s School for the Art of Secret War”, by David Stafford, 1986.

In Great Britain during the war, commando training was done in different regions, according to different terrain. The elite training camp was at Achnacarry Castle in Scotland for all allied countries. The British commandos today are the Royal Marines; they joined the army commandos in 1942.

My favourite military band is the Royal Marines. Take a look at: https://youtu.be/popbL1JuGqM

Did you know? The RAF’s nickname for all rear-gunners was “arse end Charlie”